Antarctica

“Early explorers thought penguins were fish, not expecting to find birds flying underwater—birds, we now know, that “fly” many hundreds of feet deep, hundreds of times, up to 15 hours a day, staying down up to 20 minutes at a time, propelling themselves as fast underwater as others do in the air.”

Some of the great wildlife assemblages of the world are on and around this snow and icebound continent of gigantic icebergs and vast mountain ranges. It is one of the harshest, most beautiful, most inhospitable places on earth. To survive here wildlife must make extraordinary accommodations.

Penguins here can dive 1,700 feet (518 m) and stay down for 20 minutes. Wandering albatrosses, with the longest wings of any bird, may circumnavigate the globe in a single feeding trip. Massive elephant seals can hold their breath two hours in underwater hunting trips. Ice fish survive with blood in which red cells have been replaced with anti-freeze glycoproteins. Blue whales can reach 100 feet (30.5 m) in length and weigh an average of 143 tons (130,000 kg), largest animals that ever existed on earth.

Once the climate here was more agreeable. Just 200 million years ago the Antarctic shared one great supercontinent with South America, Africa, India and Australia with flourishing populations of trees and large animals. Now, coldest temperatures ever recorded are here—193.3 degrees F below zero (-89.6°C) at Russia’s Vostok station in 1983—and strongest winds, with velocities up to 198.4 miles an hour (320 kph) when dense cold air rushes down off the polar plateau to the coast.

Ninety percent of the world’s ice containing 70 percent of the world’s fresh water carpets all but four tenths of one percent of this fifth largest, oldest continent in the world (5.5 million square miles, 14.2 million km2), with rocks dating back 3.93 billion years. The Ross ice shelf alone, world’s largest, approximates the size of France. Inland is the world’s driest desert, which paradoxically receives more solar radiation than the equator in equivalent periods—but permanent ice cover reflects 80 percent of it back into space, and frigid temperatures rob all water vapor from the air.

Antarctica is 97.6 percent uninhabitable—but on the other 2.4 percent and surrounding islands, glories of the natural world push the edge of survival limits, finding niches in which to live andreproduce in brilliant, near-24-hour daylight in the Antarctic summer. They can do this because of the Antarctic Convergence, where cooler, denser Southern Ocean waters meet and churn up warmer, more saline northern seas bringing vast nutrients upwelling to the surface at about 55 degrees latitude. This creates life—a rich plankton soup with trillions of little shrimp-like krill, part of a food chain that supports huge numbers of fish, seabirds, and sea mammals.

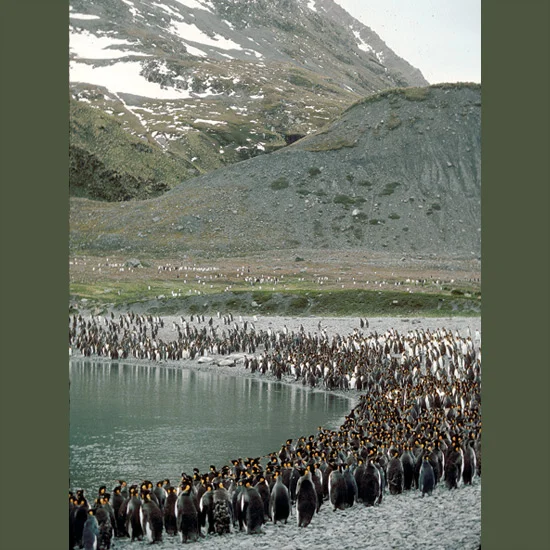

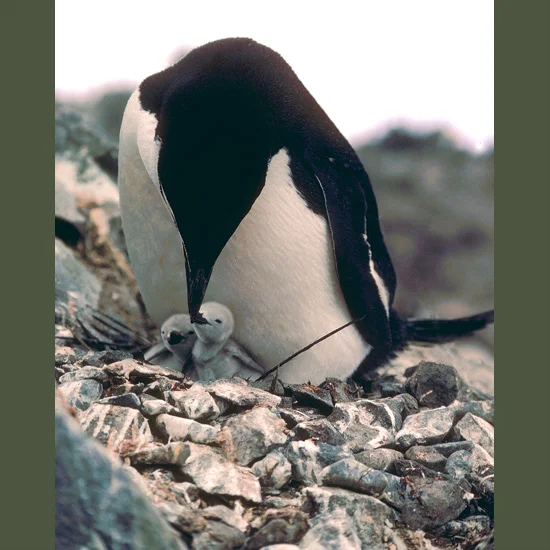

At least 45 bird species breed south of the Convergence and some on Antarctica itself—millions of Adelie, emperor, king, and gentoo penguins along with snow and Antarctic petrels and aggressive south polar skuas which make their living in large part at the expense of the others. Snow-free edges furnish avian nesting sites and pupping places for seals. Others of those millions are concentrated on subantarctic islands. Species number is small compared with lush tropics—but those that are here crowd together in some of the world’s greatest wildlife concentrations: 7.5 million pairs of chinstrap penguins; 2.5 million pairs of Adelies; up to 1.5 million pairs of kings; 3.7 million pairs of rockhoppers; 11.8 million pairs of macaronis with orange forehead tassels. Almost all must hurry to finish reproductive cycles before another six months’ cold and darkness set in, leaving only hardy Weddell seals and emperor penguins to deal with that extreme adversity.

Click image for details.

Early explorers thought penguins were fish, not expecting to find birds flying underwater, a niche they’ve secured to the point where some can fly as fast underwater as others do in the air (gentoo penguins have been timed at 22 miles an hour/36 kph). This is made possible by compact, streamlined bodies of perfect hydrodynamic design that offer no more resistance than a quarter-sized pebble. Deep-keeled breastbones, short, stiff feathers flattened over down layers insulating inches-thick skin and blubber, and paddle-like wings propel them to prodigious depths—many hundreds of feet—repeatedly, up to 15 hours a day. Legs and feet, located well back, are underwater directional controls which on land support erect humanlike posture as they walk slowly and deliberately to avoid overheating. Despite this, they can walk long distances, some species seen hundreds of miles from the nearest sea.

How they survive such dives is imperfectly understood but it is known their diving heart rate slows to perhaps five percent of normal, reducing oxygen needs which underwater are supplied partly from stores in muscles and blood. Deep-diving birds have more blood vessels and blood volume than others, and studies suggest they may be able to turn off temporarily all but essential organs, like heart and brain. Further, they have evolved solid bones, a detriment for most birds which need hollow bones to shed weight for flight, but an advantage for flightless ones that may spend 85 percent of their lives on and in water.

Within these penguin-specific adaptations are species-specific ones allowing each penguin to exploit its own niche in this hostile environment.

World’s largest and hardiest penguin is the impressive emperor—only Antarctic bird that has evolved to breed in winter in what has been called the most extreme hardship endured by any warm-blooded animal. Standing well over a yard (or meter) high, with dark heads, dark silvery backs, and orange earpatches, weighing up to 88 pounds (40 kg), emperors lay a single large egg in late summer which is incubated on the feet of the male who stands covering it with a densely feathered flap of furry skin for 66 days, much of the time in total darkness in –80°F (–60°C) temperatures and 100-mile-an-hour (160 kph) winds in some of the fiercest blizzards on the planet.

Males huddle together for warmth sharing the burden of exposure by alternating inside and outside positions, keeping precious eggs 114°F (80°C) warmer than temperatures outside. Meanwhile emperor females, energies depleted by egg production, go off to forage and return at hatching to take over from now-nearly-starved males, which then walk to the nearest sea that now, with additional freezing, may be 100 miles (160 km) away. Emperors have been known to cover 600 miles (970km) on foot in a single round-trip to feed in deeper water than any other bird—their dive record stands at 1,766 feet (535 m) for 22 minutes. For 150 more days parents alternate fishing and returning with full crops to nourish the young before they finally fledge.

About 200,000 emperor pairs breed in colonies in the Weddell Sea and Dronning Maud Land, Enderby and Princess Elizabeth Lands, and the Ross Sea. Because of their breeding schedule, they are less seen by visitors than others—and also more sensitive to disturbance.

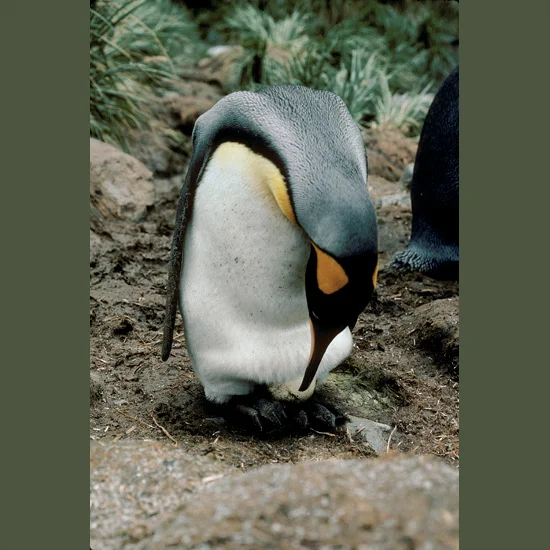

Smaller, slenderer look-alikes (with similar looks of impassive solemnity) are king penguins, from which emperors are believed to have evolved. Kings have long breeding cycles that take place in warmer seasons. Parents take turns through the Antarctic summer incubating their single egg on their feet, learning to shuffle along without losing their precious burden—and wooly chicks are reared through the winter, fledging the following summer. King penguins are deep divers, too, recorded over 1,640 feet (500 m) down, staying for 6–7 minutes. They breed colonially on subantarctic islands, sometimes in huge numbers.

Adelies with blue-black heads, white eye-rings and looks of perpetual surprise get the earliest start of the “summer” penguins. Even before inshore ice breaks up they troop sometimes 60 miles or so (100 km) to windswept coastal nest sites all around the Antarctic Continent and Peninsula, marching single-file in a curious rolling gait, one pink foot after another, tobogganing on their chests if conditions favor. Once there they settle by the hundreds of thousands and start noisy courtships, bowing and squabbling over choice pebbles (sometimes ice fragments will do) for nest structures, their collective squawks and groans audible 30 miles (50 km) downwind. After 90-day incubation and finally fledging, downy offspring, as with young of many penguins, herd into large creche groups for safety-in-numbers against predators like skuas and giant petrels. They re-sort themselves at feeding time when parents and young instantly recognize one another and reunite enthusiastically. Finally, adults subside into 20-day moults, having lost in the whole arduous process half their body weight—but in waters teeming with krill, they recover quickly.

Slightly larger gentoos with orange bills and conspicuous white eye patches prefer flatter terrain near water, handy for families which take longer to fledge. Gentoo reproductive seasons stretch out over 120–145 days, hard on parents but good for chicks which start out better able to deal with life’s adversities. An estimated 300,000 gentoo pairs gather on subantarctic islands and the Peninsula—colonies of some 100,000 pairs at South Georgia, 70,000 on the Falkland Islands, 30,000 on Iles Kerguelen.

Chinstraps, named for distinctive black neck feathers, often seen standing about on ice floes, like to forage among pack ice. Smaller than either gentoos or Adelies, they pick the highest, rockiest, most inaccessible nest sites, pulling themselves up flipper by flipper around the Peninsula and on islands south of the Antarctic Polar Front. An estimated five million of them nest on little-visited South Sandwich Islands.

Smaller macaroni, royal, and rockhopper penguins breed in huge summer colonies—5.4 million pairs at South Georgia, 2.2 million at Iles Crozet, 1.8 million at Iles Kergeulen, and two million at Heard and McDonald Islands. One million rockhopper pairs are on the Falkland Islands. Royals are only on Macquarie Island. All three have special hopping and jumping abilities enabling them to breed among tumbled boulders on exposed shores. They pursue lantern fish and small luminescent euphausiid crustaceans for food.

Nine kinds of albatross, widest-ranging seagoing birds, include the celebrated wandering, with the longest wingspan of any bird—up to 12 feet (3.66 m). This construction enables it to spend most of its life airborne, hardly moving a muscle, wings outstretched, alternately facing into the almost continuous winds of the open ocean for lift, then soaring downwind over great distances. A catch-like mechanism sets its wings so it can do this almost effortlessly for days, even months with minimal energy drain, sleeping on the wing, literally flying around the world, covering more than a thousand miles (1,600 km) in a single effortless foraging trip.

Petrels of nine species, including the giant, nest here in the millions—birds named for St. Peter because in hovering over water they can seem to be walking on it (as Scripture says this disciple did with Jesus’ help)—along with shearwaters, sheathbills, and large, heavily-built gull-like skuas, which feed on krill but also prey on other birds, including penguins.

Marine mammals include fearsome leopard seals up to 13 feet (4 m) long, which have been known to pursue humans as prey; Weddell seals up to nine feet (3 m) long weighing up to 882 pounds (400 kg), which live farther south than any other mammal, able to dive to 197 feet (60 m) and stay more than an hour; plus such other impressive seals as the Antarctic and subantarctic fur, crab-eater, and bulky southern elephant seals weighing almost a ton (900 kg) which can stay underwater two hours without breathing and have been recorded down to 3,281 feet (1,000 m). Other seals also are deep divers, the Weddell commonly hunting at depths of 1,000 feet (304 m) for an hour or more (one was recorded at 1,969 feet/600 m, where pressure reaches 882 pounds per square inch (62 kg/cm2).

Whales seasonally include Antarctic minkes, humpbacks, southern right, sperm, killer, sei, fin and, rarely, blue whales, largest animals that ever lived. A female landed at South Georgia was 110 ft (33.5 m) long.

This whole wildlife spectrum depends on an ecosystem built around some of the world’s smallest creatures, starting with microscopic plankton and ranging up to 2.3-inch (6-cm) Antarctic krill. A blue whale can consume up to 4.5 metric tons of krill a day—but almost all species here are dependent on this little shrimp-like crustacean, which fortunately is difficult to process for human consumption. It can, however, be processed for animal consumption and so has become a target for fisheries. For now, krill fishing quotas have been set by treaty and research begun on its important ecosystem niche—but overfishing is a continuing threat, as is the ozone hole, causing concern that increased ultraviolet exposure could cause gradual breakdown of this vital food-chain link. Global warming, of course, is the biggest threat of all. Proposals to explore and exploit Antarctic mineral resources in this exceptionally vulnerable environment, where almost any human activity has lasting effect and where ordinarily biodegradable waste never disappears, have now been set aside by the Environmental Protocol to the Antarctic Treaty. This bans all mining and oil development for at least the next half-century, and designates Antarctica as a “Natural Reserve, devoted to Peace and Science.”

Tourism could be a problem if it continues to grow at the present rapid rate, but most tourists and tourist ships behave well and leave no trace of their presence. Permanent scientific communities may themselves be a threat, since facilities, equipment, and daily human life processes exert constant stress on their environment.

Visitation to and around the Antarctic is by ship, arranged by or in cooperation with ecotourism groups—often museums, universities, and natural history societies—with naturalists aboard to acquaint ecotourists with background information to understand what they are seeing as well as how to see it in a way that minimizes disturbance. Many depart or return through the spectacular Drake Passage roamed by albatrosses and storm petrels sweeping along wavetops which can be relatively smooth or stirred up into 40-foot (12-m) waves with 70 mile-an-hour (115-kph) winds that send passengers looking for seasick pills. It’s a preview of the trip, since Antarctic travelers need to be aware that unpredictable weather and pack ice can force last-minute itinerary changes and adjustments at any time.

Best times are summer, starting in late November when pack ice is breaking up and birds are courting and mating. In mid-summer—December into January—eggs are hatching and chicks being fed. In late summer—January into February—chicks begin to fledge, adults are ashore moulting and whale-sighting is best.

No one trip can cover everything of interest in this vast snowy land, but highlights of possible destinations included in this site.

More about the Reserves in ANTARCTICA

Each button selection will take you to a site outside the Nature's Strongholds site, in a separate window so that you may easily return to the reserve page.

Advertisement